About a year ago, one of my coworkers proposed the idea of building our new APIs in GraphQL. He showed a pretty compelling demo and we decided to start exploring it further.

I was reading blog posts, listening to podcasts, and watching conference talks where people gave their opinions for/against GraphQL. These were pretty easy to find for the server side of things, but I really struggled to find much that dove into the mobile app developer’s perspective on GraphQL. That’s what I’m hoping to provide here.

I want to emphasize that this post is aimed at mobile app developers. There are plenty of pros, cons, and extra information for server developers which I am going to completely ignore. With that said, let’s get into it!

- What is GraphQL?

- Problems with REST APIs

- Related benefits of GraphQL & Libraries

- Downsides of GraphQL

- Downsides of Apollo-iOS

- Conclusion

What is GraphQL?

“GraphQL is a query language for APIs and a runtime for fulfilling those queries with your existing data”

Something important to note is that GraphQL is a specification. There’s no one single implementation of GraphQL. In fact, there are a bunch, in many languages and on many platforms.

Let’s look at some code to get a better understanding of what GraphQL really looks like.

In GraphQL, you define the schema for all of your data upfront. This is an example schema you would define on your server:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

type Query {

books: [Book]!

}

type Book {

id: ID

title: String!

author: Author

}

type Author {

id: ID

name: String!

age: Int

books: [Book]!

}

Here you can see it describing the graph of your data. We have the top-level query, which has books. Each book has things like a title and author. And an author has a name, age, and books.

One thing that may stand out to you is that it’s typed. You also see some exclamation points after some of the types. By default, everything you define is nullable; ! means it’s nonnull.

Now that we see how the server defines its schema, let’s look at what a GraphQL query looks like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

query getBooksWithAuthors {

books {

id

title

author {

id

name

age

}

}

}

Looking at the query above, you can see we gave it a name of getBooksWithAuthors. It’s requesting all of the books, and for each book, it’s requesting its id, title, and author. From the author, it’s asking for the id, name, and age. Notice that the Author type would also let a query request all of the books by that author, but this query is not requesting it. This is something fundamental to GraphQL; it lets you request all of the data you want from the entire schema, and only what you want.

Let’s look at what kind of data that returns to you:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

{

"data": {

"books": [

{

"id": 1,

"title": "The Very Hungry Caterpillar",

"author": {

"id": 1,

"name": "Eric Carle",

"age": 90

}

},

{

"id": 2,

"title": "Don't Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus",

"author": {

"id": 2,

"name": "Mo Williams",

"age": 52

}

}

]

}

}

Everything goes under data (There’s also a top level for errors not shown here since we don’t have any errors). Under author there are no books because those were not requested.

Problems With REST APIs

Before we talk more about GraphQL, it’s worth first talking about REST; more specifically, let’s talk about some of the problems we encounter with REST APIs. We’ll also look at how GraphQL solves some of these problems.

I again want to emphasize I’m only talking about things from the mobile app developer’s perspective, not problems server side.

These problems can be at least partially solved with REST, and I’ll try to point that out as we go. There’s not really anything in GraphQL you can’t already do with REST. If I had a sales pitch for GraphQL, it would be that these problems are solved in a standardized way, and everything comes batteries included.

There are 3 main problems I want to talk about with REST APIs:

- Lack of well-defined contracts between client & server

- Underfetching

- Overfetching

Lack of Well Defined Contracts Between Client & Server

It can be hard to know with many REST endpoints what operations can be performed. Information, such as what fields are available, the types of data for those fields and if any of those fields are deprecated, is often hard to find.

Specifications like JSON:API exist to guide developers with a standard API structure for REST responses to aid in discovery capabilities, and tools like OpenAPI/Swagger help to create an explicit contract.

While these are great solutions, they’re optional and require extra work and diligence to make sure those guidelines are being followed.

How does GraphQL solve this?

The GraphQL schema defines all of the operations supported by the API. This includes fields you can query & mutations available, as well as input arguments and responses for those. The GraphQL schema is strongly typed and all of that schema information can be queried using an “introspection” query.

The introspection query is pretty fundamental to a lot of tooling around GraphQL. Often, libraries will generate code to interact with the API for you based on that introspection query. API tester tools like Insomnia use it for autocomplete and allow you to explore the schema. It can also be used to provide better IDE tooling when writing code that interacts with the API (things like autocomplete of your queries and types).

Underfetching

Underfetching is when not enough data is included in an API response, so the app needs to make additional API requests to get all of the needed data. It’s one of the biggest problems with REST APIs that GraphQL aims to solve and one of the reasons Facebook created GraphQL in the first place.

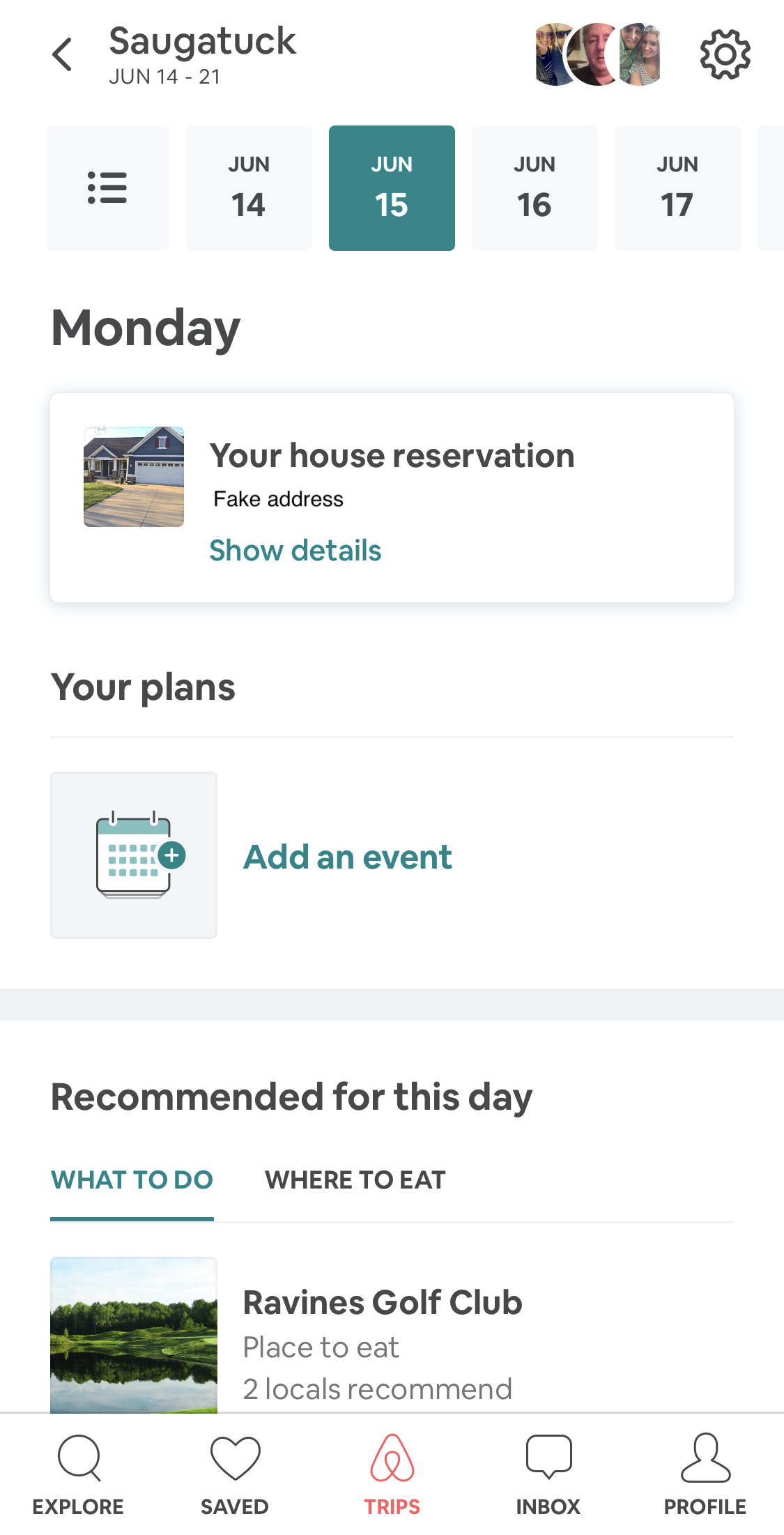

Let’s look at a hypothetical example in the AirBnb mobile app that demonstrates this (note: I do not know how AirBnb implements this page):

If you’re following REST principles very strictly, these are some of the resources we may possibly need to populate this screen:

- Trip - to get the name Saugatuck as well as the dates

- Guests - for their images in the top right

- Reservations - to get the house(s) I’ve actually reserved

- Property - the resource for the actual house that contains the house’s metadata

- Plans

- Recommended Locations

This could potentially translate into these REST endpoint calls

/trip/<id>/reservation/<id>3 * /guest/<id>/properties/<id>/plans?date=<June 15>N * /plans/<id>/recommendations?date=<June 15>N * /recommendations/<id>

# of API requests: 8 + #plans + #recommendations

That is a ridiculous number of requests to load a single page in a mobile app. If the user isn’t on a fast connection, it could have a pretty big effect on the user experience. It also brings up some UI concerns, like if parts of the UI should populate as they load in? What things should populate together? What if there’s an error requesting one of them? The code to manage all of those concerns can get a little messy.

Common ways to solve this in REST - Sideloading

“Sideloading” is when a request can provide something like an include query parameter that lists related objects to include in the response.

Ex: /reservations/\<id>?include=guests

This would give the guest information under an included key in the response.

The client still has to do some extra work to decode this response into a meaningful data structure. And unfortunately, there’s not a real standard on how to implement this on the server. So while it can be built with a lot of possible functionality, many implementations are different and have their own limitations. It also requires that the server developers account for the client’s needs ahead of time.

Common ways to solve this in REST - Specialized Endpoints

You can make an endpoint that is specific for that screen in the mobile app and return all of the data needed.

This does mean that as the client changes and requires new information, the server will have to constantly add new information onto that specialized endpoint. Having many of these specialized endpoints can also become a maintenance burden for server developers.

Common ways to solve this in REST - Leak Client needs into REST API

When the client needs just one more piece of information, it’s easy to add it to an endpoint already being called instead of having the client make another network request. For example, I really just needed the photo for each guest. I could just include their photo URL where I get their IDs so I don’t have to make another request for each.

But, what if you need one more thing after that? It’s pretty easy, over time, to keep adding more information to your endpoints, payloads can start to get pretty big, especially when fetching lists of things.

This also only accounts for a small set of scenarios when you just need an extra piece of data related to a request you’re already making.

How does GraphQL solve this?

GraphQL lets you request everything you want in a single API request.

A theoretical query for all of that information could look something like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

query getTripInfo(id: $id, date: $date) {

trip(id: $id) {

name

startDate

endDate

reservations {

imageUrl

address

}

guests {

imageUrl

}

plans(date: $date) {

...

}

recommendations(date: $date) {

name

category

numberLocalsRecommend

}

}

}

FYI: The id and date passed into getTripInfo are examples of how you would pass arguments to a query.

Overfetching

Overfetching is when the client is retrieving data that’s not needed.

Ex: I request information about the guests on the reservation so that I can get their photo url. But, it might give me back their name, date of birth, email, astrological sign, etc.

It’s a waste of resources and can potentially impact performance if it causes payloads to balloon in size.

How does GraphQL solve this?

Pretty simple, GraphQL will only return what you ask for.

Related Benefits of GraphQL & Libraries

While you can use GraphQL by handwriting the requests to your server, you’ll likely end up using a client-side library like Apollo. And you should, because there are a lot of useful features built into it.

Codegen

This library will let you write your GraphQL query like I have shown in examples above, and it will generate the Swift code for your queries and mutations, types and all!

I won’t go over how to use the Apollo-iOS SDK in this post, because Apollo has a much better tutorial here you should read.

Caching

It also comes bundled with automatic caching. Because in GraphQL the entire schema is known and defined hierarchically, it can use the names of your types, ids, path to the types in the query, and any arguments you passed in to manage a cache of the data you fetch (see this video). So if you make this query from the beginning:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

query getBooksWithAuthors {

books {

id

title

author {

id

name

age

}

}

}

That information will be cached (unless you tell it not to). So if you make that query again, it’ll pull it from the cache instead of hitting the network.

More than that, if you make a separate query somewhere else in the app, like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

query getBooksWithoutAuthors {

books {

id

title

}

}

That will also be pulled from the cache, since all of the information required to satisfy the query was cached as a result of your earlier getBooksWithAuthors query.

This is a huge time saver. I never realized how much code I was writing to manage caches until Apollo started doing it for me.

Query Watching

Because Apollo manages your cache, you can also pass your apollo client a closure when you fetch your data that it will call with your new data if the underlying cache changes.

Downsides of GraphQL

Everything has its own issues, here are some of the downsides I’ve noticed when developing in GraphQL:

- If you haven’t used GraphQL, that’s something new you need to learn.

- It’s still fairly new, so libraries around it and best practices are still being formed and solidified.

- Because much of the client-side code generation relies on introspecting the schema from a running server, when server and client developers are developing a feature in parallel, it means your server developers have to at least have a stub of the fields/mutations client developers need to use running before you write the code to talk to the server.

- The nature of GraphQL is that you have one endpoint for all of your data. However, how it gets that data is completely opaque to you as a client developer. Certain fields in the GraphQL schema may be slow to fetch because of the nature of where that data is being retrieved from, and the entire request can be slowed down or fail because of it.

Downsides of Apollo-iOS

Platform differences

The Javascript client has more features than the Android client which has more features than the iOS client.

The iOS client has picked up the pace but there are some nice things missing from it that are present in the javascript client (such as query batching)

Combine / Swift UI

If you’re an iOS developer, the support for Combine & Swift UI could be improved and made much more fluid to use.

Caching

…wait, wasn’t that was one of its benefits?

It is…and it’s great…but it also has a lot of room for improvement. One of the missing pieces is around cache invalidation. The switches are pretty broad and basically let you say whether you want to pull from the cache or not. Apollo and other client libraries could give more options for invalidating & purging data from the cache under specified conditions (such as a TTL).

Because of the lack of this feature and the default cache policy to be to always pull from the cache if available, new users can very easily fall into the trap of never updating their cache and keeping around stale data.

Conclusion

GraphQL is not a silver bullet to every problem and surely not the only solution, but it is an interesting way to solve some of the problems client developers commonly run into. Despite some of its issues, my time using GraphQL has been really enjoyable, and I wouldn’t wish to go back to using REST.